Can the German Greens save Europe, and then the world?

Green politics could be a unifying, civilizational project for Europe. But its Green parties have to see the forest behind the trees.

Benjamin: Hey Alex! After delving last week into what is holding the EU back, let’s take a look today at what could propel it ahead in the years to come. And you know what – despite recent disappointments in my own country — I think the European Greens are a pretty good contender for such a feat.

Before getting right to how they might transform the continent, our societies, the way we live, European politics and help save the climate en passant, let’s back up a bit. I think it bears mentioning that the Greens in their European manifestation are pretty unique, globally. In no other major country or world region have parties representing the protection of the environment and in favor of a pretty radical transformation of the way we live become so strong.

Granted, you have party wings or civil society movements for the environment or ecological change in most Western countries, but they struggle to set the agenda in first-past-the-post systems (e.g. the US, the UK). What’s more, the (continental) European Greens have mostly grown out of quite radical social and civil society movements.

And even though the debate about climate change is often credited to US commentators and initiatives (Al Gore comes to mind), I’d argue that it really was Europe — thanks to the pressure and agenda-setting of the European Greens — that pioneered ecological policymaking and sustainability as a yardstick for development as early as the late 1970s and ’80s.

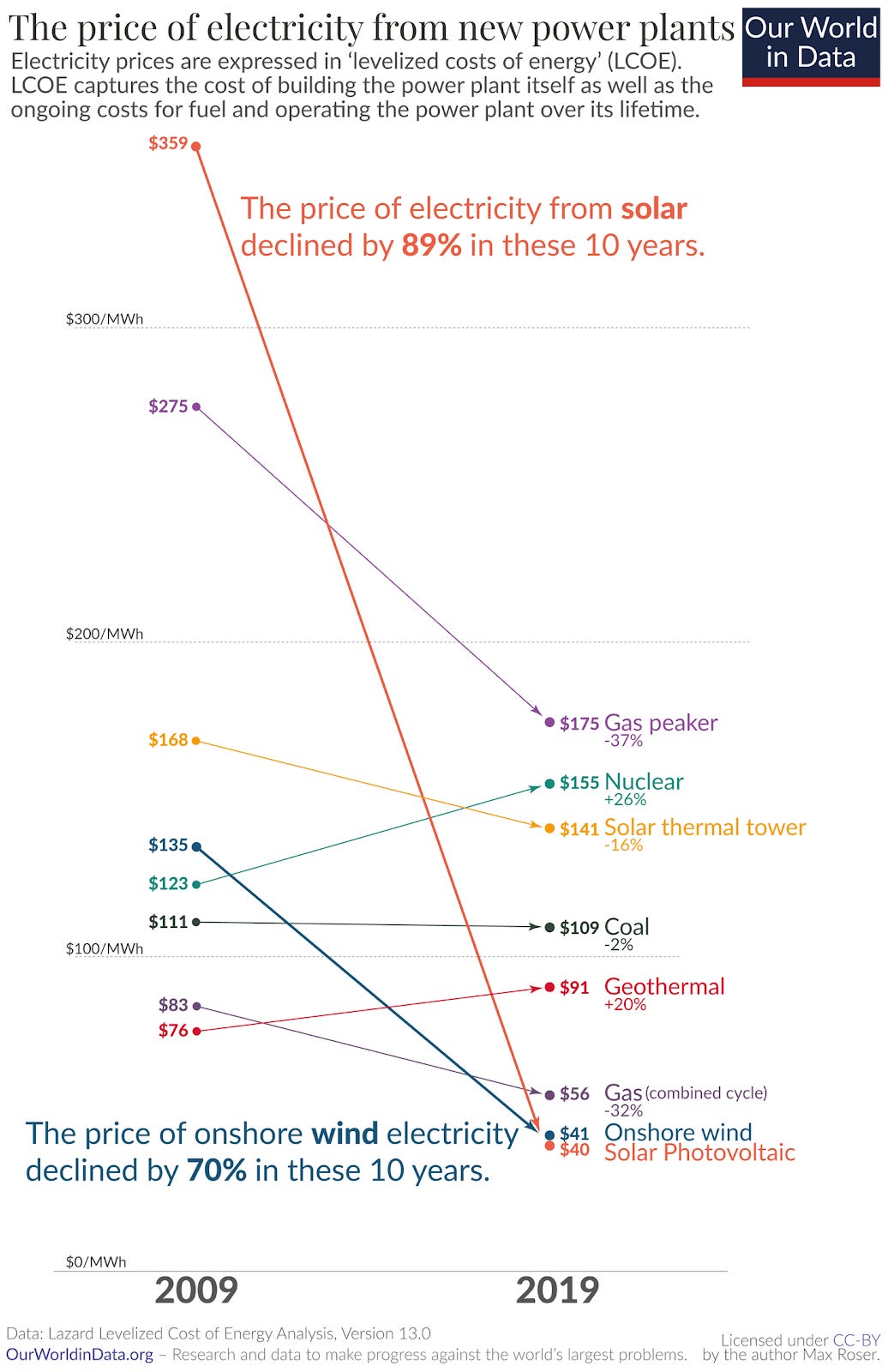

What’s more, recent breakthroughs like plummeting costs of solar and wind power would have been unthinkable without massive European government handouts. Germany subsidized the solar industry when PV was still expensive in the early 2000s and the whole world can arguably thank them for speeding up its development by 10 years or more. Thank you German taxpayers!

Now the big question is — and I know you are quite excited about it — what comes next? Can the Greens not just nudge politics from the outside but actually transform it once they get a chance to govern?

Alexander: I love the graph you just put in, because I think it’s not widely known enough that green politics are also green, as in, the color of money (well, dollars, at least). It’s profitable to be green: the hottest stocks in the market have been electric vehicles, batteries, solar, renewables… Volkswagen announced a bunch of initiatives to boost electric car production and its stock doubled over the following week. Some people will hate the fact that oodles of money will be made from the green revolution, but there couldn’t be anything better for the planet than a re-aligning of profit incentives away from dirty energy and towards clean energy.

If voters think that tackling climate change means only pain and sacrifice and de-growth, they won’t go along; if they think it means the biggest economic opportunity in human history and investing in the future, they will — and that’s clearly the pitch of Biden’s infrastructure bill.

But back to the Greens. Since they are, for the moment, most successful on a local level, here’s what I would expect from a Green mayor:

A spotlessly clean city: show me your ability to be an effective administrator and to come up with innovative solutions — public toilet facilities, showers and lockers where the homeless can keep their things, emergency housing for the homeless and a way to move them into permanent housing

Coordinate to get as much local produce as possible into school lunchrooms, ensure that there is always a vegetarian option available, and even go as far as reducing the size of meat portions if you want — but don’t ban it. People dislike being told what they can and can’t do, and how they can and can’t raise their kids

Figure out a way to provide financial assistance to people to shift from car-based commutes to electric bicycles, or to exchange their combustion engine scooters for electric scooters, and make public charging stations available

Design and put in place a logical, color-coordinated bike path scheme for easy commuting access into and around your city

Make sure public transit is running swift, efficient routes and that it’s clean and safe — if you’re the mayor of a big city, move your metro system to 24/7 operation! There’s no reason that public transit options should shut off at night.

Boost the amount of green space and reduce the amount of pavement. I mean, drastically. And not just by putting potted plants on plazas in front of buildings, I mean by cutting out pavement and replacing it with tough, resistant prairie-style grass and plants. This might be a pet peeve, but I don’t see the point in reducing the size of a street only to fill it in with...more pavement.

But once in power, Green politicians really have a burden to prove they are capable of effective governing, and to keep their eyes on the big picture — the things that matter at scale. And in order to do that, I really hope they can stay away from the kinds of marginalia-scandals that they tend to get dragged into. For example, here are some major media stories/polemics involving the Greens in France over the past few years:

I mean, I look at these stories and I see things that have zero impact whatsoever on emissions, but make Green politics look ridiculous and small-minded, when true Green politics is anything but. Aviation and Christmas trees certainly produce emissions, but focusing on these things is the equivalent of teaching someone about healthy eating by holding up an example meal that has a big slice of pizza, a sugary soda, a giant mound of fries, a donut, and a handful of M&Ms and lecturing your audience until you’re hoarse about how they shouldn’t eat the M&Ms.

Just to put things in context briefly, here’s the composition of global emissions.

So, it should be obvious where our attention needs to be focused:

Producing electricity from renewable sources and ending coal and natural gas

Electrifying automobile and truck fleets

Increasing energy efficiency in buildings

Transitioning to sustainable and regenerative agriculture globally (and here, promoting vegetarianism/flexitarianism truly is a good thing to do, but there’s a difference between ensuring vegetarian options in all school cafeterias and educating children about the impact of eating meat versus generating huge resistance by banning it)

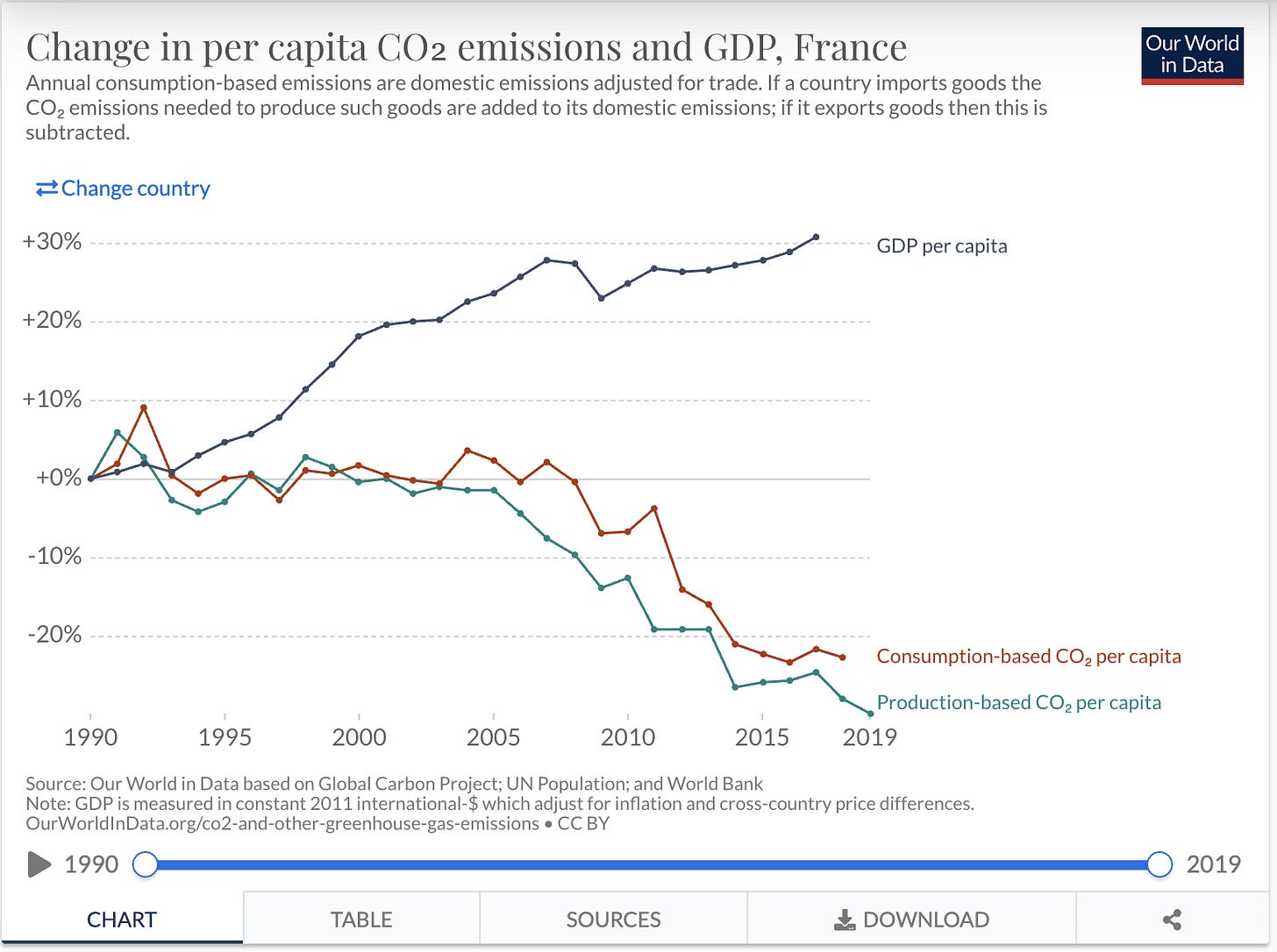

And truly tackling these four major areas requires some amount of perspective from Green politicians about where they can have real impact, because it’s often not domestically. To be clear, Europe and the United States are responsible for emitting the vast majority of historical emissions, and cuts at US or European levels still matter. But the impact of French domestic climate policies are almost nil, because regardless of how important it was historically, now the whole of France accounts for just 1% of global emissions.

So once they’ve built solid reputations in the minds of voters by effectively governing cities, where Europe’s Greens can have real impact is at a European level, by using the EU’s market power to nudge industry behavior with more stringent environmental standards and regulations (EU auto emissions standards are partly what spurred legacy automakers to invest in EVs before it was too late and they had gotten left behind) using trade deals to export tougher regulations and incentivize protecting biodiversity in places like the Amazon, implementing a carbon border tax (I have more to say on this in a minute), using public purchasing to achieve economies of scale for green solutions, and, of course, straight up investment.

Benjamin: Great points! France is indeed one of the countries that constantly gets flak for its supposedly “sluggish” economy and missing entrepreneurial and innovative zip while actually getting a lot of things right over the medium to long term. If I may add one of my favorite graphs – productivity per hour worked in France is actually at the world’s very top and has been rising faster than in the US in the last 10 years (see graphic below). I bet that’s something even most pundits wouldn’t guess off-the-cuff.

So, France decarbonized and grew successfully over these last decades and so did Europe, every country and region in their own pace.

So yes, I agree, the Greens tend to get bogged down in the minutiae of societal and environmental change. In Germany, they have even been called a Verbotspartei (the party prohibiting stuff) in the past – and that’s something you really don’t want to be seen as, as US Democrats can contest to. And some of their pet peeves, like their visceral dislike of nuclear power or their intuitive anti-capitalistic instincts also make it so much harder to scale up their actually very much en vogue solutions.

But I think it is important to see the European Greens as what they are and might become, not what we imagine them to be. As I mentioned before, they grew mostly out of civil society movements, often against big capital, big business and established parties. They were the anti-system movement before the term was coined. And they do have a deeply embedded idealist streak — which in many ways is also laudable — which seeks to not just protect the environment and climate, but also champion human rights, minority rights, build a more just society and so on.

This might seem to hold them back when thinking big about continental climate or environmental technologies, industries and transformations. But it is what they are and no truce between the Fundis (fundamentalists, i.e. idealists) and Realos (realists, i.e. pragmatists) — as the party’s wings are called in Germany and undoubtedly exist elsewhere too — will ever completely dissolve this inherent tension.

The Greens want to make a concrete and tangible difference. But they aspire to do more as well — transform society! — and in that the “Green idea” has actually more potential and power than most other contemporary ideas. I would even go as far and say it probably comes closest to a new worldview (or “ideology,” as it used to be called during the Cold War), partly supplementing, but partly also superseding elements of the currently powerful systems of liberalism, global capitalism, even representative democracy in its current form.

One small point about the current experience of a Green junior partner in a governing coalition with a Conservative party, as we have it here in Austria: Even before the pandemic, they went a long way to get a change to enact their climate and environmental ideas and “gave way” on many of the more idealistic principles, such as immigration, rights of minorities, education.

They have held fairly steady in the polls, but you see how both in the party and among the voters, the unrest is growing. Championing “protecting the climate and protecting borders,” as (Conservative) chancellor Kurz has dubbed the strategy – undoubtedly to spite the Greens, who abhor the slogan and rather see their role as “doing the best they can” under the given circumstances – will not work for the European Greens long-term.

Alexander: I can’t believe we’ve talked this much and haven’t touched more on a carbon border tax, which might be the place to start because it makes a lot of sense for the EU (in a way even free traders could, I think, be convinced of).

First, the climate necessity: cutting emissions domestically does nothing if those emissions are just being offshored — emitted elsewhere and being imported back in the form of consumer goods. Using France as an example again, we can see that when you adjust for trade, some of its emissions reduction disappears.

So if we’re serious about cutting emissions, we have to actually cut them, not just move them from one part of the world to another. You can’t put a price on carbon unless it applies globally; a carbon border tax would stop businesses from getting around that by moving production to a low cost, but high emissions location. It would also level the playing field for producers located in places with lots of renewable energy but higher costs elsewhere (labor costs, for example), and provide an incentive for economies that export to the EU to become more carbon efficient — to decouple their economies from carbon emissions, which is absolutely possible, as France itself shows (even when you account for trade).

And here’s where it is a natural no-brainer for the EU itself

Essentially what all these numbers are showing is that it takes far fewer carbon emissions to produce a dollar of GDP in the EU than it does in the US, where every dollar of GDP comes with 60% more carbon emissions attached, and China, where every dollar of GDP comes with a whopping 280% more carbon emissions! If you take into account the cost of carbon emissions, the EU suddenly looks a lot more competitive of a location to base manufacturing of consumer goods! So why isn’t it taking advantage of this?

The US and China won’t like an EU carbon border tax for obvious reasons — it removes the implicit subsidy they’re getting by taking into account the cost of pollution. But if you’re looking for a way to be “protectionist” while maintaining the moral high ground and boosting environmental reputation and soft power, I can’t imagine a better move, or a more domestically winning policy proposal to voters.

Benjamin: I want to push back though a little bit on the idea of a carbon tax, be it domestic or at the border. Phenomenally popular among experts, pundits, visionaries and economists, it is also phenomenally unpopular with most people. And there’s a reason for this, as Noah Smith lays eloquently in a recent post. He deals with the general failure of economics on climate – from not enough research to ignoring tail risks and being blind to the enormous potential of technological breakthroughs – but also hones in on carbon taxes.

Efforts in Washington State to introduce one were roundly defeated twice and Macron ran headfirst into the big debacle of his early presidency by trying to enact a tax on car fuels and facing the resistance of the Gilets Jaunes — for a measure that, frankly, did barely matter in the greater scheme of things but anger many.

So without going into too many detail why that is — do read Noah’s post, it really has some great insights — let’s just put two major reasons out there:

People intensely dislike being taxed for using energy.

And they well know that any potential benefit of such taxes will be global, while the costs are borne locally (and often even particularly by particular groups) – so a classical free-rider problem.

You can get around that by redistributing the proceeds, incentivizing more efficient energy use or a carbon border tax. But all in all, I think it might be time to move on to other big ideas that all on their own can change the game on ecology and climate change.

With this, let’s turn to a couple of very concrete proposals of the Green party that might be most consequential for Europe in the short term: the German Greens. The party is currently riding high, with recent polls for the German parliamentary election putting them in second place with 21% (compared to 8.5% of the vote they got four years ago). And their 2021 manifesto is bold and punchy in all the right places.

Jeremy Cliffe summed the crucial points up nicely in a Twitter thread (see and click below for those interested).

Other than an ambitious and comprehensive plan for an ecological transformation (lots of money for wind, solar and reducing emissions), some points jump out at me for having a potential continental impact:

Relax German debt brake on capital investment

Common EU deposit insurance

Make EU recovery instrument permanent

End unanimity requirement on EU tax decisions

New powers for European Parliament

Found a multilingual European public broadcaster

Say whaaaat? Many of these points have been on the wish lists of European federalists for decades. And they could really make a big difference, even if just implemented partly at the beginning.

So, I guess my final question is thus: Do we believe the Greens in Germans – in government or through coaxing the others – can pull this off? And will other countries go along, then?

Alexander: That would be a huge shift for Germany! And I think there is absolutely an opportunity for the Greens to become a unifying, federating movement — one that can bypass other political divisions. I’d even go so far as to say they might be able to do what Macron wanted to do: jettison 20th century notions of left and right and promote the type of “civilizational project” that he alluded to in an interview with Le Grand Continent from last fall. (I think that project has to integrate three components of our political zeitgeist — protectionism, ambitious fiscal policy, and climate action. Which is why I disagree with you on a carbon border tax, which I think would be treated by voters as quite different from a fuel tax).

But returning to France again, a few years ago a nonprofit called More In Common (Or Destin Commun, in French), did a really broad social survey and found just this consensus around green politics. Basically, in the various countries they’ve studied, they’ve identified 5 different political families beyond the normal left-right division we’re familiar with. And without going too much into all of that, the highlight from their France report is that — in France, at least — these 5 very divided political families all sort of converge on the idea that ecology could be a common social project (figure 1) and opportunity (figure 2) that goes beyond the urban-rural divide (figure 3) that’s upending pretty much all advanced democracies.

But in order to do that, it can’t drift into all of the other issues that divide political families! And that’s what the Green Parties need to internalize, which I think the German Greens have and the very divided French Greens/left have not. Is everything connected? Yes, of course — migration politics are linked to climate politics, which are linked to taxation and trade and investment… But a common project can’t just recreate all of the political divisions that are there in the first place. Everything is connected, but there are margins and windows, and we can address the big problem facing us, emissions, climate change and biodiversity loss, and creating a green economy, without losing our grip on it by bringing in everything under the sun.

Benjamin: The Greens — first in Europe, then elsewhere — were and are most successful by shifting the narrative, bringing new ideas and pushing others to adopt them as “mainstream.” That may sometimes feel as too little, too late, or too slow, but it actually works astonishingly well when looking back.

Who would have guessed in the 1980s and 1990s that the climate, the environment and ecology would become the unifying force that many see in our societies? And who would have guessed in the 2000s how quickly businesses would get on board too, once the wind had shifted decisively?

So I agree, all the ingredients are there for “ecology to become a unifying, federating movement” as you call it. And in some way, I wish for Green parties to be bold and put their visionary ideas out there provocatively, to keep being the avant garde of this movement — it’s often the best way to push ahead.

Others may adopt their policies, but the Greens themselves will need to keep some of their idealism and socio-cultural aspirations.

So I would rephrase the question and ask: How can the Greens govern successfully without giving in to petty squabbles, but also without giving up their soul and turning into a techno-ecological party only? Because that is not what they are, nor what they want to be.

(And I know you like the techno-ecological label and idea, but I think it’s important to see how alarmed many Greens would be if they were just reduced to that.)

Alexander: They’re unlikely to be reduced to that. They’re too divided about things like capitalism and labor markets and how much federalism is desirable for Europe and whether Russia and China are Europe’s potential friends or systemic foes. But even in the places where they don’t succeed at becoming an actual political force, I think they’ll still succeed at this broader thing that is both civilizational project and social narrative, the way the actual Green Party in the US has been a political failure (other than playing spoiler in close elections — first Ralph Nader in Florida in 2000, then Jill Stein in 2016), and yet at the same time its core agenda has been adopted by the mainstream, which is evident in the fact that Biden’s infrastructure bill is the Green New Deal in many ways, if not in name.

I’ve been thinking about why so many people are echoing the refrain of “the left just doesn’t inspire anymore” (and I’m talking about the European left), and I think it’s because it’s not talking about big things. I mean, what really is the battle of the European left these days? It’s not the implementation of the modern social democratic welfare state, like it is in the US. European societies are imperfect, but the basic ingredients are all there. And it’s hard to inspire people with “we need to improve what we’ve got,” you know?

But tackling climate change, that’s big. There’s a narrative arc. There’s a goal to be reached, challenges to overcome, societies to mobilize. Can you rally Millennials and Gen Z around “we’re going to protect your future retirements by reforming and strengthening the social security system”? I don’t really think so. But saving the world? Yeah, I do.